The real objective of REPowerEU is to slash the share of imported gas in the EU’s energy mix by doubling decarbonisation efforts.

Outlook 2022+

The impact of the war in Ukraine will give momentum to energy transition.

It is difficult to predict the future now, but faced with the choice between rebuilding the past (lost fossil fuel supply) in other locations and investing in redirecting demand to sustainable sources, we go for strengthening the energy transition as it creates energy security in the new dimension of zero-carbon economy, moving away from energy commodity markets and cyclical fluctuations in commodity prices.

-

103-3

We began last year’s Outlook with the statement that the COVID-19 pandemic had not altered the development challenges facing the oil and gas and petrochemical industries, but it forced a change in strategic and business thinking. We said that the all-important challenge for businesses would be to switch the strategic thinking from preparation for an anticipated change to rapid response to unexpected developments.

It did not take long for this statement to be verified. In the fourth quarter of 2021, international energy commodity markets saw a price surge of a previously unthought-of scale. Along with the price hikes came questions about how an oversupply in those markets swiftly turned into an undersupply, how long it will take to return to equilibrium, and how this process will unfold. Those developments caused a fiery debate on the pace of the transition and on whether we should not slow down for a while and shift investment to conventional sources. An argument has been raised that high prices, limiting the affordability of energy for low-income groups, are posing a threat to energy security here and now, so restoring the security now is more important than the energy transition, i.e. security tomorrow.

Being one of the companies that have made a commitment to achieve climate neutrality by 2050, we presented our own diagnosis of the situation, pointing to underinvestment in the natural gas market relative to the growing needs for renewable energy support as the reason for the imbalance. Based on this, we proposed that the energy transition process needs to be reinforced by aligning its pace with the physical capacity for redirecting demand to renewables. We will explain this in more detail further in this report.

The outbreak of war in Ukraine on February 24th 2022 and the political and economic sanctions imposed on Russian energy exports have brought energy security to the forefront of attention. Indeed, the continuity of energy supplies (oil, liquid fuels and natural gas) came under threat in many locations. Meanwhile, everyone has been affected by the rising prices in global energy markets driven by the loss of Russian supplies, limiting the availability of energy to businesses and households, which is particularly difficult for developing countries and many emerging economies. Yet again, the reality has verified the thesis we put forward a year ago about the need for businesses to prepare for unexpected changes. In practice, the ability to respond quickly requires the availability of diversified supply sources and of appropriate reserves in many areas, i.e. it is the outcome of carefully considered investments that enhance the security of an organisation in a dynamically changing environment.

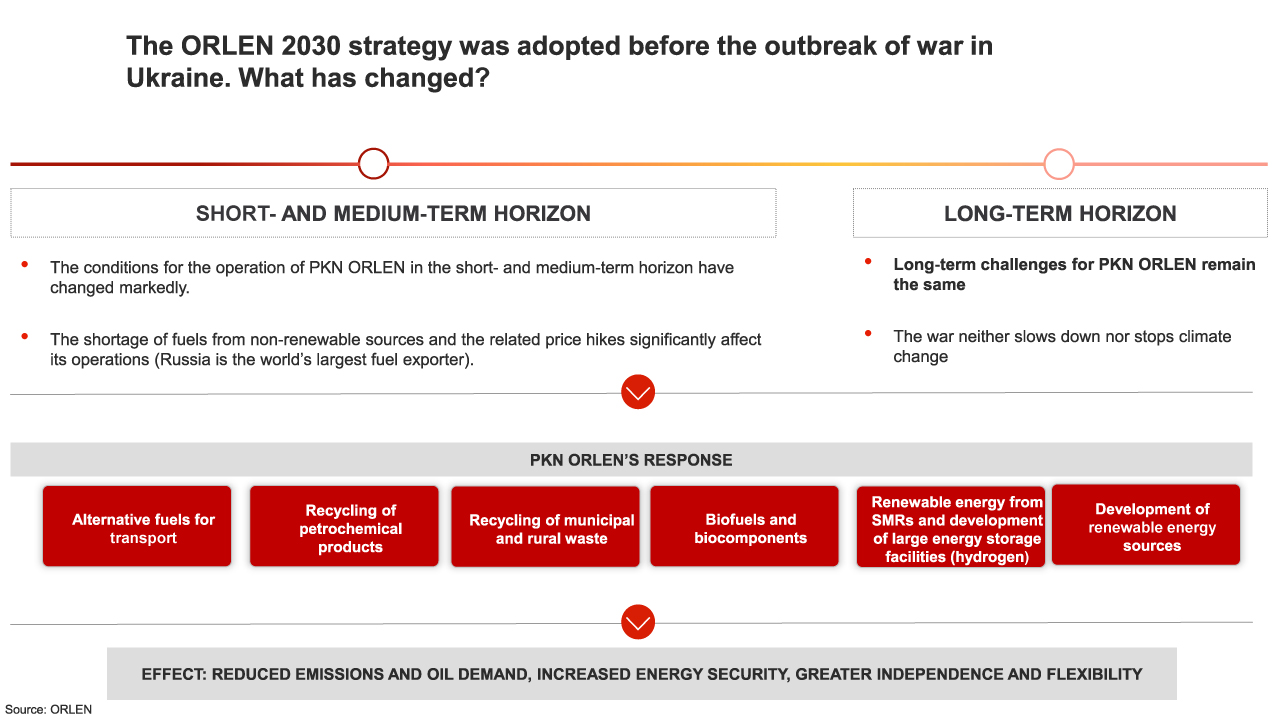

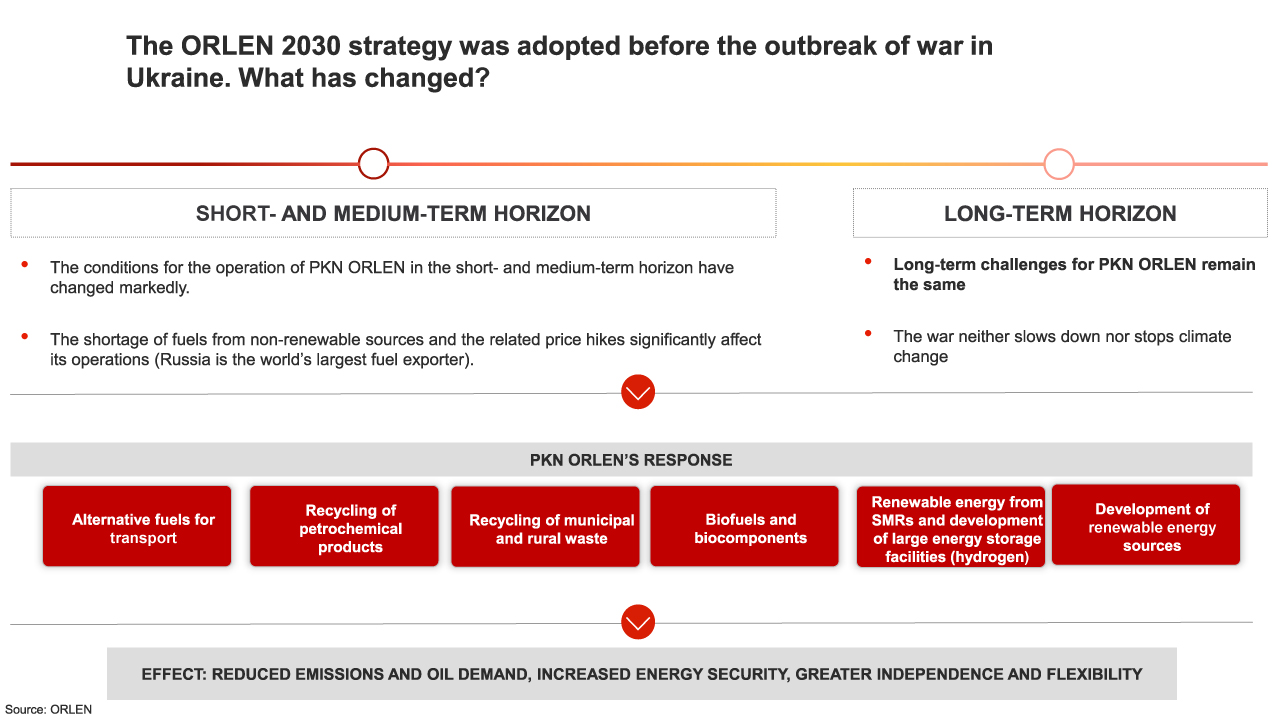

At PKN ORLEN, we did our job and ensured the possibility of supplying our refineries from various directions and of processing various types of crude, which is of crucial importance to maintaining continuity of fuel and petrochemical production. In line with the ORLEN 2030 strategy, through the acquisitions we have completed and are now finalising we are effectively building a multi-energy group, thus improving our position in many segments of the energy sector, both in terms of primary energy sources and usable energy. Having diversified our supply sources and with a well thought-out long-term strategy addressing key industry challenges (which have been accelerated rather than changed by the outbreak of war) in place, we believe that we are well prepared in terms of energy security and that we continue on the right path towards energy transition. Understanding the need for engaging simultaneously in initiatives with different time horizons, we believe that the conflict between security and energy transition is only apparent.

Loss of energy security can be measured by the scale of destruction to demand, that is the size of decrease in energy consumption forced by supply disruptions and high prices. Restoring energy security, impaired by the effects of war and sanctions imposed against Russia, requires substantial investment. As we consider where the investment should be made, let us look at energy security in terms of time. There is no doubt that the current state of each country’s energy security is the outcome of a process of strategic decisions and investments made in a distant past, from one to a few decades ago, because this is the time span corresponding to the cycle of construction and useful life of fuel and energy assets. Restoring the security after it has been lost will also take time, as this generally involves investment. Because of the ongoing energy transition, decisions to invest in restoring energy security are not easy, since there may be no business rationale for fixing an energy system from a distant past. In addition, one needs to consider the opportunity cost as investing in the energy sector will have an impact on the safety of our children and grandchildren. The war, which is being fought here and now, make us focus on current threats and on the search for quick solutions. However, it does not affect in any way the relevance of the long-term challenges brought by climate change, which, considering the maturity cycle of innovative technologies, need to be addressed today in order to secure the availability of affordable energy in a few decades.

Supply shock

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a momentous event, ending Russia’s role as an energy superpower and undermining, albeit to varying degrees, energy security of all countries around the globe. It brings to mind the 1973 oil crisis, which changed the world.

The war in Ukraine is by far a more powerful shock to global energy markets, as it affects not only oil, but also natural gas, coal, and liquid fuels. There is no doubt that what we are seeing is another world-changing event. Since the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia has become strongly integrated into the global economy. Those ties are breaking down now and Russia is tying up with China and becoming more dependent on it. Russia was an energy superpower: the largest exporter of energy resources. Now, it will still be a major supplier, a major producer, but its days as a superpower are numbered. Russia is going to lose its most valuable market: Europe. It will also be cut off for some time from Western investment and, more importantly, from Western technologies. It will lose markets and its share of those markets.

Europe is taking steps to cut off its energy supply from Russia as soon as possible. This applies to three energy carriers: crude oil, natural gas, and liquid fuels. Sanctions on their exports to Europe will reduce the size of supply globally as redirecting Russian resources to markets outside Europe: China, India and Asian countries, is not fully practicable and requires investment and time.

Among energy carriers, oil will be the least severe problem, because the loss of its global supply as a result of sanctions is the smallest and crude can be delivered to Europe from other directions. The balance in the oil market is supported by reduced demand from China due to COVID-19, increased production in the US, and the announcement of the release of oil from strategic reserves held by the International Energy Agency and the US government. Oil supplies from Iran may also begin once an agreement on the nuclear treaty is reached.

A much bigger problem is fuels, especially diesel oil, which is imported to Europe in large quantities from Russia.

The imbalance in the diesel oil market in the fourth quarter of last year was caused by additional demand from the power industry. Now, with the summer holiday season beginning in the Northern Hemisphere, supply shortages are also seen in the case of gasoline. The strong growth in diesel oil and gasoline prices in international markets relative to the price of crude should prompt refiners to increase oil throughput and the supply of these fuels, but what stands in the way is insufficient refining capacities. Since 2020, more than 3.5 mbd of refining capacity has been shut down in response to insufficient demand and low profitability, mainly in the US but also in Europe. The tension in fuel markets and high fuel prices relative to oil may persist for some time, depending on the ‘resilience’ of global demand to high prices. In developed countries, this resilience improved as a result of growth in disposable incomes and fuel price declines after 2014, reducing considerably the share of fuel cost in households’ budgets. The share of transport costs in companies’ spending has also gone down worldwide.

The persistently high prices of liquid fuels are felt most strongly by developing and emerging economies with low per capita incomes. Coupled with high food prices, fuel and energy prices pose significant risks to their economic growth.

The most serious challenge in Europe is the supply of natural gas, which used to flow abundantly from Russia by pipelines. The lost gas supply cannot be made up for without investments by sourcing it from other directions, and some time will pass before the effects of investments will be seen. The Netherlands could increase gas supplies from the Groningen field, which was closed due to earthquakes. The Dutch government stated that the field could be brought on stream again only in the event of a threat to energy security, which appears to be the case now. The list of priorities includes LNG and investments in expanding suppliers’ liquefaction capacities, which are currently an obstacle to increasing LNG exports from the U.S. In this context, Poland is generally in a better position to diversify its gas supply than most EU countries, and has LNG infrastructure and interconnectors to support its neighbours (especially the Czech Republic and Slovakia) in discontinuing gas purchases from Russia.

RePowerEU – Europe's response

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its evident readiness to use gas supplies as a political weapon have made Europe rethink its energy strategy. The REPower Plan ,published on May 18th 2022, affirms the EU’s commitment to end gas imports from Russia by 2027 and focuses on fast forwarding energy transition as a key mechanism to achieving this goal.

RePowerEU, being a continuation of a much less detailed document published in early March, sets out specifically how Europe can reduce its demand for natural gas and includes a series of ambitious proposals that build on the „Fit for 55″ package of legislattion. Successful implementation – leading to accelerated rollout of renewables, reduced demand for energy and diversification of gas supplies – will depend not only on further actions at the EU level but, more importantly, on specific steps taken by individual Member States.

In addition to reducing gas demand by the currently estimated 116 bcm per annum by 2030 following the implementation of the ‘Fit for 55’ plan from 2021, REPowerEU envisages taking additional measures to bring down annual gas demand by an extra 118 bcm over the same period.

REPowerEU gives prominence also to hydrogen. Based on the new 45% target for renewables, REPowerEU provides for a massive scaling-up of renewable hydrogen use by 2030: the 2030 targets for renewable hydrogen would rise from 50% of industrial demand planned under the ‘Fit for 55’ package to 78% and from 2.6% to 5.7% in the case of transport fuels. Demand for renewable hydrogen would increase from 5.6 million metric tonnes per year (MMt/y) to 20 MMt/y, of which 10 MMt/y would be imported.

The main amount of EUR 300bn in public funding includes only EUR 20bn of new funds; most of the funding will depend on the EU Member States’ willingness to contract additional debt by using the EUR 225bn of the previously agreed funds for the period after the end of the COVID programme. EU’s support will play a certain role, but the main burden of implementation will rest on the Member States and their respective budgetary situations.

One should remember that Russia will not just stand by and do nothing about the EU gradually phasing out its dependency on Russian gas – gas from Russia will most likely stop flowing long before 2030. Such a decision by Russia would force the EU to take contingency measures, such as reducing gas supplies to industry and state interventions in the EU gas market. The success of REPowerEU in achieving diversification of supplies, the pronounced acceptance of increased coal-fired generation for a certain period of time, and proposals of public communication campaigns to encourage lower gas consumption by households will put the EU on track to cushion the impact of a gas supply cut from Russia, although it will be economically painful anyway.

Undermined energy security

Following the outbreak of war in Ukraine, energy security has not only been brought back to the list of challenges, joining the energy transition, but has become a primary challenge for many countries.

A crucial element of physical security is the actual diversification, that is securing a viable alternative to existing sources of supply and quick substitution of supply sources and fuels when and as needed.

The war in Ukraine and sanctions levied against Russia have revealed the level of European countries’ physical energy security. In Poland, the diversification based on a defined security strategy and completed projects expanding the country’s ability to source oil and gas from various directions, together with the strategic reserves system, raised the level of physical energy security to the highest possible level. PKN ORLEN plays a leading role in diversifying sources of oil supplies, ensuring that there are no disruptions in the production of fuels in Poland.

Another dimension of energy security is the availability of affordable energy. This includes the ability to develop domestic energy resources at economically viable costs by launching specific projects across the country, and the ability to acquire reasonably priced energy resources under contracts and through trading activity. In open market economies, where goods move freely between countries, the prices of oil, liquid fuels, natural gas or coal depend on the supply-demand relationship on international markets. Prices on international energy commodity markets are driven by the availability of products. When the market starts to be undersupplied, prices go up and limit the availability of a given commodity for those who cannot afford it, so those who can are able to buy it.

The war in Ukraine once again shook the market foundations of energy security. NATO members and countries that condemn Russia’s military aggression have severed diplomatic relations with and imposed political and economic sanctions on Russia. Authoritarian countries that continue to cooperate with and object to applying economic and political sanctions against Russia are on the other side of the fence. Because Russia was the largest exporter of fossil fuels in the world, the impact of the war hit international fuel markets and the wave of price spikes was also seen in countries far away from the hostilities, including those with low per capita incomes. Therefore, sharp rises in energy and food prices carry the risk of social tensions and conflict. It should be remembered that the increase in energy and food prices after the great financial crisis of 2008/2009 sparked off social unrest and conflicts in more than 40 countries across the globe, including in countries exporting energy commodities.

Soaring prices are already pumping up pressure on governments to intervene on oil markets, compounding uncertainty and increasing price volatility. Oil markets have always been susceptible to political influence and government decisions. These days, the range of actual and potential measures that governments can take to influence the market is very extensive. The release of International Energy Agency (IEA) reserves is a perfect example here, showing an unprecedented level of market intervention. In addition, the market has to contend with Beijing’s unpredictable decisions on further lockdowns due to COVID-19, the possibility of Europe slapping new energy sanctions on Russia, the tense and opaque negotiations on the Iran nuclear deal, and with the unintended consequences of governments’ attempts to protect consumers from rising transport fuel prices.

The problem with natural gas

The roots of the gas market crisis which lasted until the end of September 2021 can certainly be traced back to underinvestment in that market relative to actual needs, without probing into any deeper reasons. This was the standpoint presented by Fatih Birol, Executive Director of the International Energy Agency[1]. He argued that the gas market is going through a classic supply crisis associated with the unprecedented surge in demand recovering after the pandemic, which the supply is unable to keep up with. A remedy that could help avoid such crises in the future would be to invest in the gas market and its infrastructure, while building up adequate stocks.

When we try to pinpoint reasons behind the underinvestment, i.e. to understand why there is not enough gas available on the market, there are strong arguments that such reasons may lie in internationally uncoordinated efforts involving alternative energy sources.

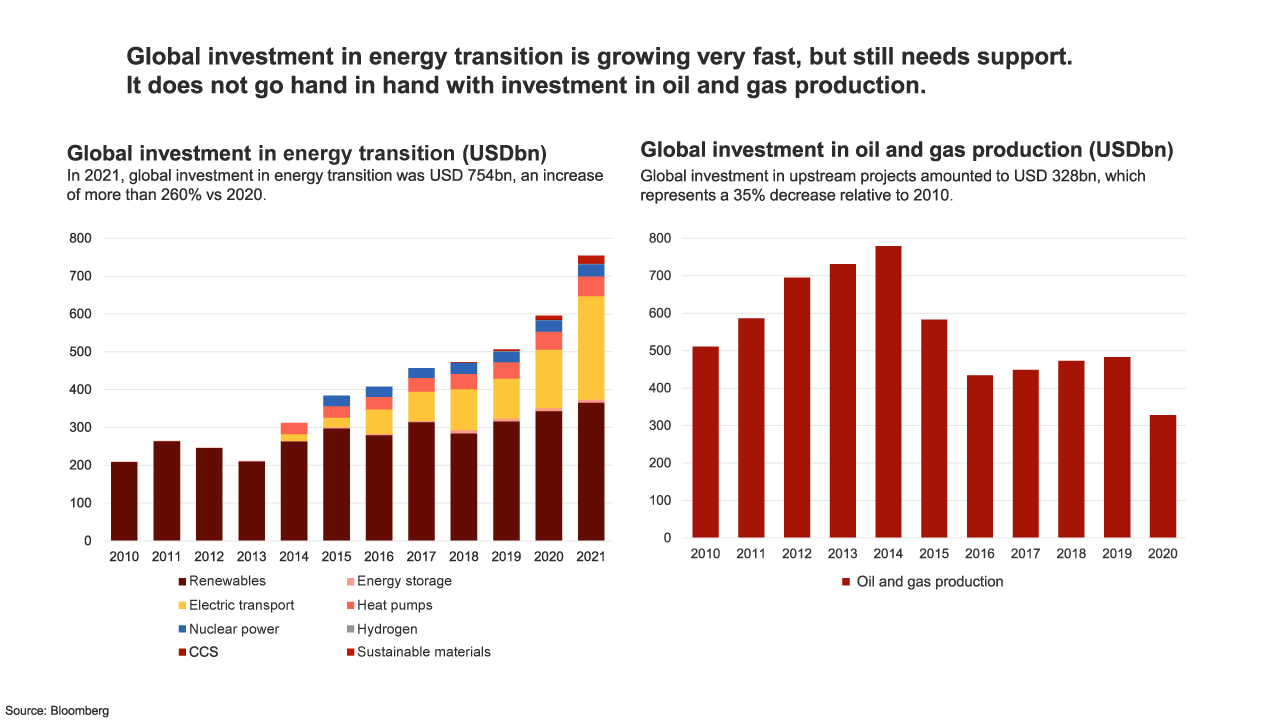

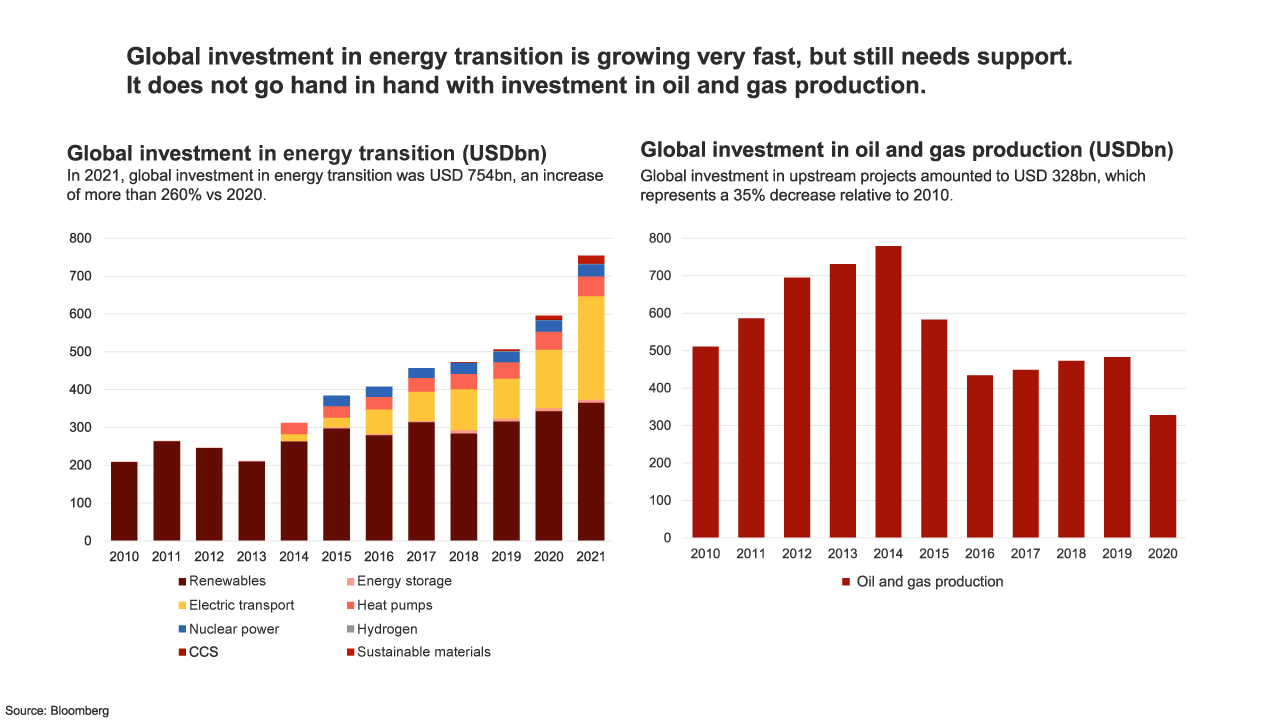

The regulatory and financial incentives for EU operators to accelerate investment in renewable energy are not matched by any requirements to secure the continuity of energy supply. The default role was played by the gas capacity along with the liquid (until the time of crisis) LNG market, which supplies the entire world. But the market regulators resolving to step up the energy transition not only refused to afford support, but actually discouraged investment in that market. As a result, investment in oil and gas production globally has fallen by more than a third over the past decade.

1 https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/europe-world-need-draw-right-lessons-from-todays-natural-fatih-birol/?utm_content=buffer5e2e9&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter-ieabirol&utm_campaign=buffer

(accessed on Feburary 3rd 2022)

This is why Professor Dieter Helm of Oxford University argues that “The current crisis was very predictable, and its causes run deep. A series of simple myths have been spun out to the wider population, which simply are not true. It is not yet true that renewables are cheaper than the main fossil fuels once intermittency is taken into account. Simply ignoring the need for back-up in claims about renewables costs will not make them go away. On the contrary, two inconvenient facts remain. The first is that whilst intermittency was not much of a problem when there was very little wind capacity in the system, it now very much is. Now that wind and solar make up a much bigger share of total capacity, this really matters – and it needs a much bigger investment in back-up capacity. The economics of that back-up capacity is seriously impaired by renewables at times producing wholesale prices of zero – when the wind is blowing well and the sun is shining – and very high prices when they are not. In the UK, in the old fossil-fuel and nuclear system, total capacity requirements were of the order of 70–80 GW. For a system where wind and solar sometimes can produce all the energy demanded and sometimes very little, that firm power capacity needs to remain in place, plus the wind turbines and solar panels too. We need a great deal more capacity to meet any given demand.” And he puts it bluntly: “That has to be paid for by someone. Pretending that the costs do not exist, or that they will all go away in a blitz of new technologies anytime soon, is a dangerous climate change narrative. Worse still is to just assume that it can all be paid for by borrowing. That just means that not only are we not prepared to pay the costs of decarbonisation, but we want to dump both the costs and the climate change onto the next generation.”[2] After all, at the end of the day, it is us consumers who pay for everything.

Also Rice University researchers in their report published at the end of last year took a realistic look at what is needed for the global energy transition to succeed. They warn that too rapid a phaseout of fossil fuels could have the opposite effect – stranding climate progress in the so-called ‘valley of death’. “Pushing to defund fossil fuels – before lower-carbon resources can credibly ‘fill the gap’ – risks destabilizing a global energy- food-water-human well-being nexus that, sufficiently perturbed, would likely delay energy transition efforts for decades.”[3]

The pace of the transition, certainly a strategically important issue, has preoccupied us for long[4]. According to scientific consensus, the world can keep global warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius on condition that it achieves carbon neutrality by 2050. This in turn requires a reduction in global carbon emissions of at least 45% relative to 2010 by 2030. Given that the trend in global carbon emissions has remained flat over the past decade,[5] the energy transition should be sped up considerably. This argument has grown stronger since the outbreak of war in Ukraine.

2 http://www.dieterhelm.co.uk/regulation/regulation/luck-is-not-an-energy-policy-the-cost-of-energy-the-price-cap-and-what-to-do-about-it/ (accessed on Feburary 3rd 2022)

3 https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/global-energy-transitions-looming-valley-death/ (accessed on Feburary 3rd 2022)

4 https://www.money.pl/gospodarka/impact21-jak-przyspieszyc-zielona-transformacje-6706094159637152a.html (accessed on Feburary 3rd 2022)

5 https://www.carbonbrief.org/global-co2-emissions-have-been-flat-for-a-decade-new-data-reveals (accessed on November 9th 2021)

How to accelerate progress of the transition without creating market tensions?

Development is a long-term process, ideally free from recessions. How to avoid a recession? Economic theory recommends the same approach as coaches do when preparing athletes for a marathon. Grow at a rate dictated by the growth in economic potential rather than by consumer and investment demand. If you want to complete the race, you had better run at a pace suited to your capability and physical fitness. Want to run faster? Become fitter. Otherwise, when you accelerate, you will need to stop running to recover strength. As a consequence, you will cross the finish line later, covering the entire distance more slowly.

It is very much the same with the energy transition, being a long-term development process. It should unfold at an optimum pace: any acceleration throwing the important markets into imbalance should not be seen as a welcome part of it. Rapid renewable capacity expansion without securing continuity of supply leads to overheating and transition recession, i.e. growth rather than a reduction of CO2 emissions. As demonstrated by the market today, higher CO2 emissions translate into higher emission allowance prices, thus encouraging investment in renewables and discouraging investment in traditional power generation, which is currently the only reliable security against supply disruptions. This becomes more and more of a vicious circle, of which energy security is the victim. It may thus be worthwhile to consider whether the soaring prices of emission allowances are not a warning signal.

We already know that green transition looks different for the financial sector than it does for the real economy.

The consequences of their varying elasticity have sent ripples through the energy and fossil fuel markets, triggering a global spike in inflation. The lesson we are just learning from the energy markets is that the pace of transition should be determined by what is the bottleneck area, being much slower and resistant to change.

Such bottleneck area is global consumption, of both energy and raw materials, and so action needs to be focused there, especially that lower emissions from any consumption always have the effect of reducing global emissions.

The difficulty in steering global consumption through a green transition is that the transition costs must be addressed. Pretending they do not exist is a road to nowhere. Having internalised environment and climate protection costs, green consumer products and services will be more expensive than their currently available counterparts. However, they will be cheaper than their brown counterparts, bearing the additional cost burden of CO2 emissions. Such costs must be fully passed on to consumers to persuade them to choose green products instead of more expensive brown ones. Failing that, the consumption structure will not shift in the desired direction, causing a supply-demand imbalance across product markets as manufacturers, burdened by the cost of emissions, will phase out brown products faster than consumers are willing to part with them.

Zero-carbon consumption does not have to be more expensive if the inevitable price increase is accompanied by a change in lifestyles and consumption patterns.

Consumer spending is important, not prices. Applying higher future prices to the current consumption structure is a mistake, because higher prices will force a shift in the mix of consumed products and services.

To avoid being left out of pocket, consumers must be able to buy sustainable products in small portions, exactly when they need them and as much as they can consume (on-demand economy). A task facing the industry is to create new business models underpinned by new technologies, mostly digital, to help consumers meet their needs at a lower cost. Possible solutions include adopting the product-as-a-service model and managing consumer demand.

The rising costs and transforming business models will primarily force a reduction in the per capita consumption of raw materials, which can be achieved in a circular economy. This is a formidable challenge for the industry, involving a change in the enterprise valuation model in the transitional period (as a decline in sales profits will not be fully offset by an increase in profits from rendering of services).

One vehicle of the green transition, which takes long to become ripe for the picking, is innovative technologies. Technologies of the future have first to be invented, tested, and scaled up. As they mature and develop, new technologies may involve some unwelcome effects of scale. How many wind turbines can the Baltic Sea accommodate? How to dispose of old non-recyclable wind turbines? Technologies are about supply, whereas preparing a green product offering is the role of the industry. Entering the world of new technologies brings with it a new kind of uncertainty, formerly unknown to companies using ready solutions.

Companies do a good job picking out government incentives to invest in new technologies. However, it would be better if such incentives were technology neutral, supporting every solution equally, without preference or prejudice. This would bring a wider range of solutions to the market and mitigate regulatory risk (failure of the solution the government chose to support). At the other end of the market are consumers, who make the choice. They decide whether to switch to a green product right away or to hold off for a while. Will they benefit financially? New solutions must be attractive and affordable to consumers around the world. They must take account of the purchasing power gap between the global north and the global south. Interregional transfers will be a necessity.

We must also remember that consumption cannot be fully decarbonised due to technological reasons, but also because of economic and social factors. This is why the global goal is not decarbonisation but rather climate neutrality, i.e. reducing the carbon footprint to zero on a net basis. Emissions that cannot be reduced must be captured by natural means or using the CCS/U technology, and then stored or returned to production.

A transition that creates jobs in developing countries with the largest population growth, generating sufficient income to fund consumption. From this perspective, it is pretty obvious that energy transition pathways in the global north will differ from those in the global south. In the richer global north, a reduction in consumption-driven emissions (including the amount of materials consumed) should be deep enough to enable an increase in consumption in the global south. This will require massive financial transfers between the regions, as well as dedicated products, services and business models.

Besides, we are talking about processes that take place on the global scale. Countries around the world make their own decisions about how to achieve an energy transition, thus affecting the global gas, coal, and oil markets in an uncoordinated manner. The consequences of their sovereign actions are felt around the globe. This is why energy transition needs to be a synchronised and coordinated effort.

Strengthening of energy transition in PKN ORLEN's strategy

Summary

- The impact of the war in Ukraine is set to give momentum to energy transition. Accelerated phase-out of fossil fuels will help reduce emissions and improve energy security.

- The attractiveness of upstream production and refining segments is temporary (high margins). Therefore, it should be made the most of by investing in the promising areas identified in the ORLEN2030 strategy.

- High prices of fuels will accelerate the phase-out of oil-based fuels in transport. Demand for alternative fuels (electricity, biofuels, hydrogen) will grow.

- We are witnessing a shift in the role of natural gas in the European Union. REPowerEU requires a deeper cut in gas consumption to eliminate its imports from Russia.

- Renewables which can replace natural gas (hydrogen, biomethane) will gain in prominence.

- The importance of municipal and rural waste recycling (generation of hydrogen and biomethane to supplement domestic gas production) is on the rise.

- Nuclear power generation, especially SMRs and large energy storage facilities (hydrogen) will be increasingly important.

- Investor appetites are shifting towards utilities and low-carbon power generation associated with RES (on-roof solar PV systems).

- The development of digital technologies will enable active management of energy demand.

- Petrochemicals are still viewed as an attractive investment opportunity – improved competitiveness.

- Recycling of petrochemical products is becoming more and more important.

- Retail – the test bed of digitisation – offers extensive opportunities for growth.

- Innovation, Research & Development will play an increasingly crucial role – long-term competitive advantages are developed in house, by experimenting with new technologies and business models in reliance on one’s own resources and at one’s own risk.

Dr Adam B. Czyżewski

Chief Economist, PKN ORLEN

May 2022